A preview from our Winter issue.

The numbers are in, and they are devastating. The Pew Research Center’s “A Portrait of Jewish Americans” portrays a community in existentially threatening dysfunction. Some of the numbers are already well-known: Intermarriage rates have climbed from the once-fear-inducing 52 percent of the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey to 58 percent among recently married Jews on the whole. (The rate would be about 70 percent if one were to leave out the Orthodox, who very rarely intermarry.) Only 59 percent of American Jews are raising their children as Jews “by religion,” and a mere 47 percent of them are giving their children a Jewish education. And the communal dimension of Jewish life, which has for millennia been the primary mainstay of Jewish identity formation, is all but gone outside the Orthodox community; only 28 percent of those polled believe that being Jewish is essentially involved with being part of a Jewish community.

Stakeholders in the status quo are running for cover, questioning the Pew methodology, and quibbling with its results. But one fundamental conclusion is inescapable: The massive injection of capital into the post-1990 study “continuity” agenda has failed miserably. Non-Orthodox Judaism is simply disappearing in America. Judaism has long been a predominantly content-driven, rather than a faith-driven enterprise, but we now have a generation of Jews secularly successful and well-educated, but so Jewishly illiterate that nothing remains to bind them to their community or even to a sense that they hail from something worth preserving. By abandoning a commitment to Jewish substance, American Jewish leaders destroyed the very enterprise they claimed to be preserving.

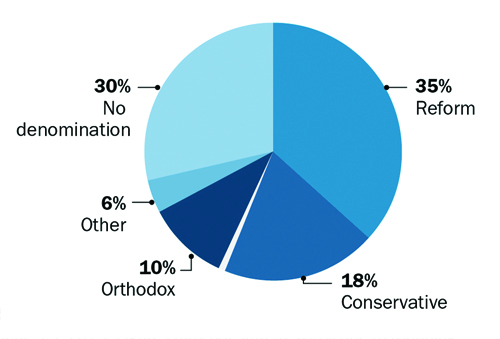

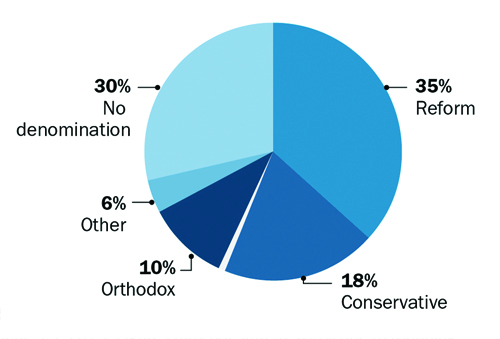

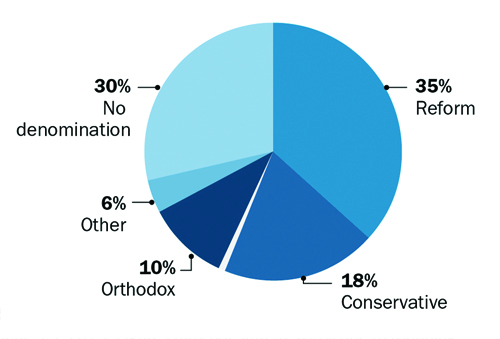

Jewish denominational identity. (Courtesy of the Pew Research Center. From “A Portrait of Jewish

Americans,” © 10/1/2013.)

Nowhere is this rapid collapse more visible than in the Conservative movement, which is practically imploding before our eyes. In 1971, 41 percent of American Jews affiliated with the Conservative movement, then the largest of the movements. By the time of the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey, the number had declined to 38 percent. In 2000, it was 26 percent, and now, according to Pew, Conservative Judaism is today the denominational home of only 18 percent of Jews. And they are graying. Among Jews under the age of 30, only 11 percent of respondents defined themselves as Conservative.

Barring some now unforeseeable development, the movement’s future is bleak. As Rabbi Edward Feinstein, one of the movement’s leading pulpit rabbis noted at the recent post-Pew United Synagogue Convention, “Our house is on fire . . . If you don’t read anything else in the Pew report, [you should note that] we have maybe 10 years left. In the next 10 years, you will see a rapid collapse of synagogues and the national organizations that support them.”

The likely demise of Conservative Judaism greatly saddens me. I was raised in a family deeply committed to the Conservative movement. My paternal grandfather, Rabbi Robert Gordis, was in his day one of the nation’s leading Conservative rabbis, a long-time member of the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary, one of the Conservative movement’s most articulate spokespeople, and president of the Rabbinical Assembly. My mother’s brother, Rabbi Gershon Cohen, was chancellor of JTS from 1972 until 1986. There are other Conservative rabbis strung along our family tree, me among them. I came of age in the Camp Ramah system, was ordained at JTS, and was the founding dean of the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies, the Conservative movement’s West Coast rabbinical school. Even if I’ve long since meandered to a different religious community, the impending demise of Conservative Judaism means the disappearance of the world that shaped me.

My personal sadness, though, is of no account compared to the loss this represents for American Jewish life. Not long ago, it appeared that Conservative Judaism might be an option for those for whom the rigors of Orthodoxy were too great, but for whom Judaism as a conversation framed around profound issues and texts was still compelling. That was the era in which Conservative rabbis, reasonably conversant in Jewish classical texts and able to teach them to their flocks, could mitigate the increasingly pervasive tendency of liberal Judaism to recast Jewishness as an inoffensive ethnic version of American Protestantism-lite.

But this reframed Judaism, saying little and welcoming all, has proven irresistible to an American Jewish generation to which difference is offensive and substance is unnecessary. Gabriel Roth’s response to the Pew report in Slate is a case in point. He notes, inter alia, “Here are some of the things I cherish about Jewishness: unsnobbish intellectualism, sympathy for the disadvantaged, psychoanalytic insight, rueful comedy, smoked fish.”

That Jewish self-conception must be offensive to Protestants and Catholics, who are entitled to believe that they, too, are capable of unsnobbish intellectualism, sympathy for the disadvantaged, and psychoanalytic insight. But the real issue is that Judaism recast as a variant of American upper-crust social sensibilities simply says nothing sufficiently significant to merit survival. Indeed, Roth then predicts quite convincingly, “For my grandchildren, the fact that some of their ancestors were Jewish will have no more significance than the fact that others were Welsh.”

Conservative Judaism was supposed to have prevented the American Jewish slide into this abyss. Despite the triumphalism so in vogue in contemporary American Orthodoxy, the fact remains that a plurality of American Jews will not adopt the halakhic rigors that lie at the core of Orthodox communal expectations. There are theological, moral, intellectual, and “lifestyle” reasons for that. For those people for whom Orthodoxy was not an option, it was Conservative Judaism that offered a vision of Jewish communities colored by reverence for classical Jewish learning and for Jewish tradition, even if with a somewhat looser adherence to its particulars.

Sans Conservative Judaism, the vision of a traditional, literate non-Orthodox Judaism will be gone. And that is a terrible loss, for Orthodoxy no less than for American Jewish life at large.

Given the enormity of the loss, it behooves us to ask, “What went wrong?” There were many factors, of course. America’s openness proved a Homeric siren-like allure too powerful for many to resist. And then, with no courage of whatever convictions they might have had and animated primarily by fear, leaders of all varieties of liberal Judaism decided to lower the barriers in order to further constituency retention. They expected less of their congregations, reduced educational demands, and offered sanitized worship reconfigured to meet the declining knowledge levels of their flocks. In many cases, they welcomed non-Jews into the Jewish community in a way that virtually eradicated any disincentive for Jews to marry people with whom they could pass on meaningful Jewish identity.

But those, of course, were precisely the wrong moves. When people select colleges for their children, professional settings in which to work, or books to read, they seek excellence. Lowered expectations mean less commitment and engagement; less education means greater ignorance—why should that attract anyone to Jewish life? It didn’t, as it turns out.

Much ink has been spilled on these and other causes of the Conservative movement’s demise, and this is not the place to review the arguments. But one factor has been almost entirely overlooked, and it ought to be raised, because if we can articulate where Conservative Judaism went wrong, we can begin to describe some of the characteristics of what one might hope will arise in its place.

Because many of the leading Conservative ideologues of the mid-20th century had hailed from Orthodox circles, it was important to them to sustain the claim that Conservative Judaism was halakhic Judaism. Yes, they acknowledged, Conservative Jewish life looked very different from Orthodoxy (women could assume roles that they could not in Orthodox settings, for example), but that was simply because Conservative Judaism was reclaiming the “dynamic Judaism” to which the rabbis of the Talmud had actually been committed. It was Orthodoxy that was a corruption of authentic Judaism, they insisted, and Conservative Judaism had come on the scene to protect (“conserve”) the genius of legal fluidity that had always been key to rabbinic Judaism.

That argument was not entirely wrong. In somewhat different and obviously much-softened language, it has even been adopted by some leading modern Orthodox rabbis. Nor was what doomed Conservative Judaism the incessantly discussed vast gulf in practice between the rabbis and their congregants. What really doomed the movement is that Conservative Judaism ignored the deep existential human questions that religion is meant to address.

As Conservative writers and rabbis addressed questions such as “are we halakhic,” “how are we halakhic,” and “should we be halakhic,” most of the women and men in the pews responded with an uninterested shrug. They were not in shul, for the most part, out of a sense of legally binding obligation. Had that been what they were seeking, they would have been in Orthodox synagogues. They had come to worship because they wanted a connection to their people, to transcendence, to a collective Jewish memory that would give them cause for rejoicing and reason for weeping, and they wanted help in transmitting that to their children. While these laypeople were busy seeking a way to explain to their children why marrying another Jew matters, how a home rooted in Jewish ritual was enriching, and why Jewish literacy still mattered in a world in which there were no barriers to Jews’ participating in the broader culture, their religious leadership was speaking about whether or not the movement was halakhic or how one could speak of revelation in an era of biblical criticism.

Who really cared? Very few people, it turns out.

To the irrelevance of the central argument at the core of much Conservative discourse must be added its hypocrisy. These men and women of the pews were not talmudic scholars, but they were sufficiently educated and had enough common sense to know that if combustion on Shabbat was prohibited, then driving on Shabbat simply had to be a violation of Jewish law. So when Conservative Judaism declared, in its (in)famous 1950 “Responsum on the Sabbath” that it was permissible to drive to synagogue on Shabbat, Conservative Jews smelled a rat. Whatever Conservative Judaism was advocating, it was not Jewish “law.” They appreciated, perhaps, being told that they were not sinning when driving to the synagogue (not that “sinning” was a terribly central facet of their religious worldview), but they also knew that a game was being played.

Some rabbis called it like they saw it. Rabbi Emil Schorsch (father of Ismar Schorsch, who later served as chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary) asked, “Too many of our people do not want to observe the Sabbath, whatever excuse or reason you may give them. Why should we play ball with this insincerity?” But by and large, the Conservative movement succumbed to the pretense that Rabbi Schorsch the elder was too honest to sustain.

Slowly but surely, the rank and file understood that they were witness to what was more than a bit of a charade. Yes, a small intellectual elite subscribed to Conservative Judaism’s unique brand of halakhic life coupled, for example, with principled gender egalitarianism, but the vast majority of kids who came back from Camp Ramah or from the movement’s Israel programs seeking a halakhic community found themselves, in the space of a few short years, in the bosom of Orthodox synagogues (a significant and telling phenomenon, however statistically small, that flies entirely under the Pew radar). And those who remained in the movement, by and large, encountered a conversation that simply did not address their need to define their place in the cosmos.

So self-referential has the Conservative conversation become that the movement today continues to insist on the centrality of Jewish law, without so much as even trying to make a case for it. In its recent much-ballyhooed publication The Observant Life: The Wisdom of Conservative Judaism for Contemporary Jews, a massive 981-page tome, Conservative Jews are exposed to discussions of kashrut and Shabbat but also pornography, employing gays in synagogues, neutering animals, and biodiversity. The Table of Contents is both revealing and devastating; astonishingly, there is not a single chapter on why they should care about halakhain the first place.

Instead, the conversation that hasn’t worked for half a century is trotted out once again. In the volume’s Foreword, Chancellor Arnold Eisen reflects the historical bent of most of JTS’s chancellors and writes:

“Law and tradition” has long been the watchword of “Positive-Historical” or Conservative Judaism. That was particularly so in early decades when the movement’s major thinkers in Germany and America struggled to explain what was unique about their approach to Judaism . . . [Solomon] Schechter and [Zacharias] Frankel would have welcomed The Observant Life, I believe; I certainly do.

Eisen is one of America’s greatest Jewish scholars. Yet half a century after Conservative Judaism began its precipitous decline, his language with respect to the centrality of history as a central facet of Conservative Judaism is identical to what my grandfather was saying in the 1940s. Given all that has changed in the world, who is likely to read the 981 pages that follow?

Could matters really have ended otherwise? To be honest, I don’t know. But we also didn’t really try. Looming unasked in Conservative circles is the following question: Can one create a community committed to the rigors of Jewish traditional living without a literal (read Orthodox) notion of revelation at its core? Are the only choices that American Jews have Orthodoxy (modern, or less so), radicalized liberal Jewishness with its wholesale abandonment of tradition, or aliyah to Israel?

American Jews deserved more choices, and a Conservative Judaism with a different discourse at its core might have provided one. Conservative Judaism could have been the movement that made an argument for tradition and distinctiveness without a theological foundation that is for most modern Jews simply implausible; instead of theology, it could have spoken of traditional Judaism and its spiritual discipline as our unique answer to the human need for meaning.

Imagine that instead of discussing whether or not it was halakhic, Conservative Judaism had said to its adherents something like, “None of us come from nowhere. Not so very deep down, we know that we do not want to be part of an undifferentiated human mass, loving all of humanity equally (and therefore loving no one particularly intensely), abandoning the instinct that our people—which has been speaking in a differentiated voice for millennia—still has something to say to humanity at large.”

Imagine that instead of inventing arguments that somehow sought to maintain an effective claim for revelation even after the movement’s infatuation with biblical criticism (which, of course, undermined the most obvious argument for the authority of Jewish law), Conservative Jewish leaders had invoked an argument similar to that of the Catholic theologian Charles Taylor, who reminds his readers:

What is self-defeating in modes of contemporary culture [is that they] shut out history and the bonds of solidarity . . . I can define my identity only against the background of things that matter . . . Only if I exist in a world in which history, or the demands of nature, or the needs of my fellow human beings, or the duties of citizenship, or the call of God, or something else of this order matters crucially, can I define an identity for myself that is not trivial.

That is the sort of argument that mainstream Conservative Judaism (which celebrated Abraham Joshua Heschel’s poetic take on Jewish life but marginalized him from the halakhic-Jewish practice conversation) could have and should have invoked. Life is about asking important questions (think the Talmud), and yes, much of contemporary American culture is self-defeating. And meaningful life is about demands and duties. “That is why we are here,” Conservative leaders could have said. “We need bonds of solidarity, duties of citizenship, and yes, the call of God. Otherwise, we are trivial.”

The movement never wrote the way that Taylor writes, and it never taught its rabbis to think or to speak with that kind of deep existential and spiritual seriousness. It could have, though. It could have invoked Jewish intellectuals, like Michael Sandel, who wrote in Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, that:

[W]e cannot regard ourselves as independent . . . without . . . understanding ourselves as the particular persons we are—as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons and daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic . . . For to have character is to know that I move in a history I neither summon nor command, which carries consequences nonetheless for my choices and conduct. It draws me closer to some and more distant from others; it makes some aims more appropriate, others less so.

Arguments such as those would have put the most human, most self-defining, most existentially significant questions of human life at the center of Conservative Jewish discourse, and the result might well have been a very different prognosis for the only movement that was primed to raise these questions. It is true that young Americans might still have opted for triviality; but they might also have returned to something less vacuous as they grew older and wiser.

The moral of the sad story of Conservative Judaism is this: Human beings do not run from demands that might root them in the cosmos. They seek significance, and for traditions that offer it, they will sacrifice a great deal. Orthodoxy offers that, and the results are clear. Liberal American Judaism does not, and it is paying the price.

Those who will live in the aftermath of Conservative Judaism’s demise will live in an American Judaism diminished and robbed of an important voice. This is not the moment for gloating or for self-congratulation—even within Orthodoxy. This is the moment to begin to ask the question that the Pew study puts squarely in front of us: If Orthodoxy is intellectually untenable for many, and liberal Judaism is utterly incapable of transmitting content and substance, is there no option for Jewish continuity other than Israel? There must be. Those who care about the future of the Jewish people had better embark now on the search for what it might be.

Daniel Gordis is senior vice president, Koret Distinguished Fellow, and chair of the core curriculum at Shalem College. His new book, Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul, will be published by Nextbook.

No comments:

Post a Comment